As a supplement to our historical overview, we present here information on a selection of distinct Ukrainian American communities in New Jersey. This is not even remotely exhaustive: the intent is to portray a small part of the diversity of Ukrainian American community life. It will also try to situate these stories within the broader histories of these locations and in the broader context of Ukrainian Americans in the United States in general. Ukrainians were, of course, just one of many groups who settled in the ancestral territory of the Lenape People, from the early Dutch and English colonists, to the innumerable other groups who would arrive from elsewhere in Europe and around the world over the subsequent centuries.

This page presents a sampling of urban and suburban communities. Rural communities are presented elsewhere.

Jersey City

When the first Ukrainians (Ruthenians) came to Jersey City in the 1880’s, they were part of the “New” Immigration that made its way to the Garden State from 1880 to 1920. Adventurous newcomers arrived in increasingly larger numbers from southern and eastern Europe from countries including Italy, Poland, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They would find well established communities of British, Germans and Scotch-Irish of the “Old Immigration” who had come to this industrial town during the period 1840-1880.Shaw, Douglas V. Immigration and Ethnicity in New Jersey History. Trenton, N.J. 1994. New Jersey Historical Commission, Department of State. pp. 17-48.

Jersey City in the 1880’s was a bustling manufacturing and port city, fueled by New Jersey’s overall dynamic economy, with an expanding industrial base and a constant demand for skilled and unskilled labor. Jersey City newcomers found work in the steel, tobacco, and pencil factories often located within walking distance of the tenements they occupied in the Paulus Hook section also known as “Gammontown”. The neighborhood lay within the shadow of the Statue of Liberty and nearby Ellis Island, which had become the gateway to America for many immigrants from Eastern Europe.

For Ukrainian immigrants, the “Sugar House” on Washington near Morris Street became a major employer. This waterfront warehouse on the corner of Essex and Washington Streets on the south side of the Morris Canal was designed in 1863 and later became part of the American Sugar Refining Company.Dowd, Kevin. Downtown Jersey City - The History Behind The Sugar House. 2010. (Archived web page captured Feb. 29, 2024) By 1907, the Refining Company employed over fifteen hundred workers and occupied four city blocks, where it refined raw sugar imported from around the world. In 1910, many of the Ukrainian immigrant men who lived in the nearby tenements on Morris Street worked there, including Semen Sawchyn (the great uncle of Michael Buryk, the primary author of this essay), who arrived in 1907.

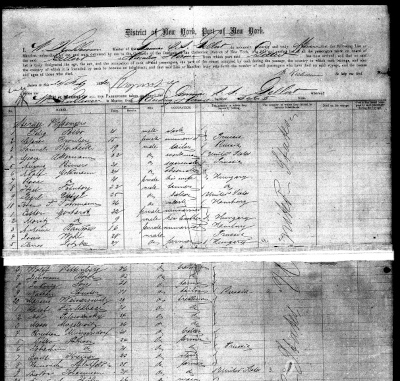

Passenger manifest showing the arrival of Paul (Pavlo) Filak

One of the first Ukrainians to emigrate to Jersey City was a Lemko from Luhiv (now Ług, Poland, province of Horlytsi/Gorlice in Galicia). Paul (Pawlo) Filak was born in 1845 and his occupation was listed in immigration records as “cartwright” (i.e., wheelmaker). Other Lemkos soon followed in his footsteps and by 1887 there were 17 Ukrainian families in Jersey City. This number grew to 150 by 1899.Lutwiniak, Theodore. “Ukrainians Active Here Since 1879”. The Jersey Journal, Jersey City, New Jersey, May 2, 1942, p. 103.

Religion played an important role in the establishment of Ukrainian community life in Jersey City. In 1884, the Rev. Ivan Wolansky (Volanskyj) arrived in Jersey City and considered establishing a Ukrainian Greek Catholic parish there. But, he had been invited by a group of Ruthenians in Shenandoah, Pa., to establish a parish there. Since they paid for his passage to the U.S., he left for Coal Country to establish St. Michael’s Church in Shenandoah as the first Greek Catholic Church in the U.S. He returned to Jersey City in 1887 and established Saints Peter and Paul Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church for the local Ukrainian community and a small, wooden chapel was built on Henry St. in the Heights.“Saints Peter and Paul Ukrainian Catholic Church: A History”. 21 unnumbered pages, pp. 1-3. In 1887-1987: Commemorative Book of Saints Peter and Paul Ukrainian Catholic Church. Jersey City, N.J., 1987. Later a large, five-domed brick church was built at the corner of Sussex and Green Streets in 1902.

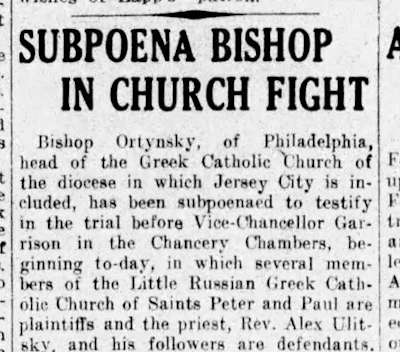

The parish continued to grow, but would eventually split. In 1907, Saints Peter and Paul Church as a parish of the North American Ecclesiastical Mission under the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church in Russia was established on Grand Street where it stands today. In 1915, a group of Ruthenian families in the Lafayette section of Jersey City formed their own church which became known as St. Mary’s Byzantine Catholic Church. This religious conflict would play out in many Ukrainian-Ruthenian communities throughout the U.S. in the early part of the 20th century.

The Birth of Svoboda and the Ukrainian National Association

In 1889, Fr. Hryhorij (Gregory) Hrushka arrived in Jersey City to become the first permanent pastor for Saints Peter and Paul Parish. Besides putting the parish on a firm footing, he was very active in local civic and community affairs. In 1890, he established a Ukrainian cooperative store, the “Ukrainian Trade Market”, located at 102 Morris St. The grocery store was established to protect Ukrainian immigrants from unscrupulous merchants. In his apartment on nearby Warren St., Fr. Hrushka began publishing the Ukrainian newspaper “Svoboda” (freedom) on September 13, 1893 with the help of Denys Saliy, Sidor (Isidore) Ferenc, Denys Pirch and Denys Holod. This newspaper became an important channel in the Ukrainian immigrant community for the exchange of information, ideas and civic engagement. It continues its publication today.“Saints Peter and Paul Ukrainian Catholic Church: A History”, p. 3.

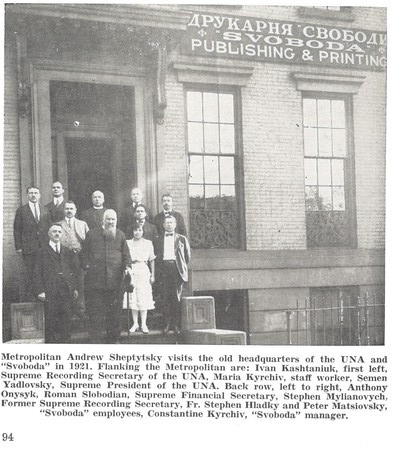

Metropolitan Andrew Sheptytsky visits the old headquarters of the UNA and ‘Svoboda’ in 1921

On December 1, 1893, Fr. Hrushka helped form a political club headed by Pawlo Stupynsyj. This organization would lead to the establishment of the “Ruthenian (later Ukrainian) National Association” in February 1894 in Shamokin, Pa. The group was established to give a solid and effective structure to the growing Ukrainian American community. The UNA later established its headquarters in Jersey City, where it purchased a property at 83 Grand Street in 1910. This building would house the UNA’s administrative offices, and also the editorial and printing facilities of “Svoboda”. By the end of 1913, the UNA (then still called the “Little Russian National Union”) would have 372 affiliated branches in 20 U.S. states and 2 Canadian provinces, including 31 branches in 13 different cities across New Jersey. Almanac of the ‘Rus’kyi Narodnyi Soiuz v Amerytsi’ (‘Little Russian National Union of America’) for the Ordinary Year of 1914

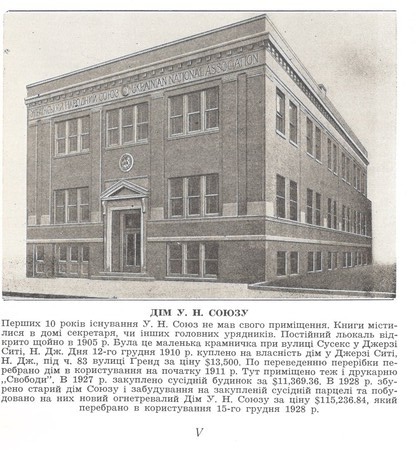

The ‘new’ 1928 UNA building in Jersey City

In 1927, the UNA purchased the neighboring building to 83 Grand Street, razed both structures, and built a large, modern headquarters building which opened in late 1928. The UNA continues its community work today with its headquarters in Parsippany, N.J.

Prosperity and Roles in Civic and Cultural Life

Ukrainians continued to arrive in Jersey City in the early part of the 20th century until World War I broke out in 1914. As second generation was born and grew up in this urban Ukrainian village. The “Old” immigrants in Jersey City became acquainted with the newcomers through their many public performances announced in the Jersey Journal newspaper and other local press. As World War I dragged on, Ukrainians organized fundraisers for humanitarian aid for Ukraine. At the end of the war when it appeared that Ukraine might have an opportunity to finally secure its independence, Ukrainians in Jersey City were active in promoting this cause and lobbying the U.S. government. During the 1920’s, mass rallies were held in the city to publicize the plight of Ukrainians as the western part of the country (eastern Galicia) came under the jurisdiction of Poland.“The Jersey Journal”, Jersey City, New Jersey. Nov. 12, 1921, p.6 and Nov. 14, 1921, p. 9.

An important focal point for the community was the Ukrainian National Home. As early as 1894, Fr. Hrushka hoped to establish a center for the local community, but various conflicts slowed its establishment until September 1918. Then it was located at 1012 Newark Avenue and became a community hub for cultural and social events.“Saints Peter and Paul Ukrainian Catholic Church: A History”. p. 12. The building at this location was sold in 1927 and a new Ukrainian National Home was in the Heights section of the city in 1932. There was a general revival of Ukrainian community life in Jersey City during the 1930’s and the new Ukrainian Home played a major role in it.

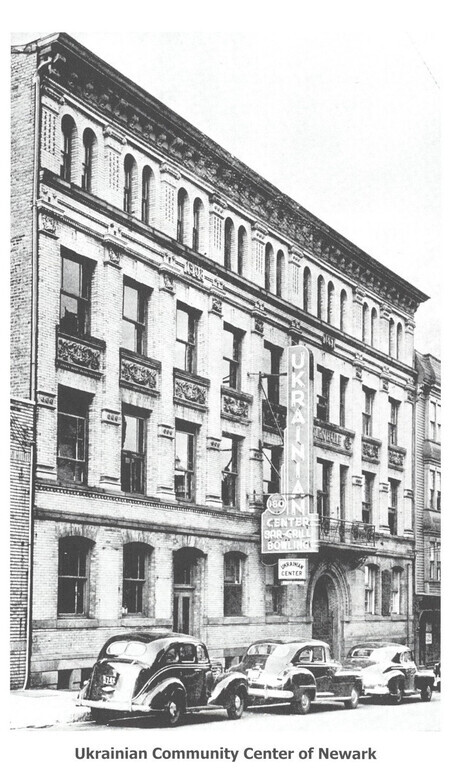

Newark

Newark is the largest city in New Jersey and was founded in 1666. The city thrived during the Industrial Revolution and became a manufacturing hub through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Various waves of immigrants provided the unskilled and skilled labor to power these industries. The Irish arrived in the 1820’s to build the Morris Canal and Germans came as refugees from the failed revolution of 1848. They would become a third of the city’s population by 1865. African Americans migrated from the South in the late 1800s and especially during the World War I factory boom in Newark. Almost 22,000 Blacks arrived between 1920 and 1930.“History of Newark: A Walk Through Newark with David Hartman and Historian Barry Lewis” Between 1880 and 1920 Newark’s Italian-born population grew from four hundred to twenty-seven thousand. Eastern Europeans began to settle in increasing numbers in Newark during the early 1900s, initially in what is now known as the Ironbound section.

By 1899, 145 Ukrainians had settled in Newark. Newark had numerous factories including in leather and textile goods and this offered them a regular source of employment for the unskilled. Most of them came from such areas of Western Ukraine as Lisko, Ternopil, Zbarazh, Rohatyn, Berezhany, Pidhaitsi, and Staryi Sambir.

Religious Diversity Among the Ruthenians

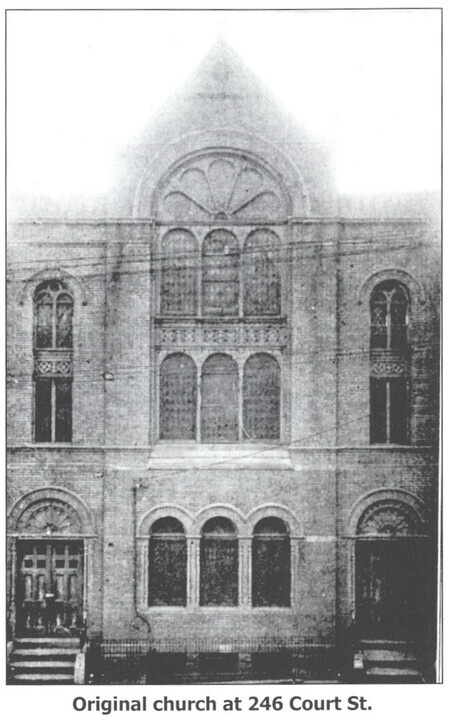

Original church building of St. John the Baptist Ukrainian Catholic parish on Court Street, Newark

Early on, Ukrainians attended church services in nearby Jersey City and Elizabeth. In 1907, the Greek Catholic Church of St. John the Baptist was founded in a building at 246 Court Street in Newark purchased from the First Evangelical Association for $17,500. This was in what is now the Central Ward. In 1911, the Very Rev. Peter Poniatishin became pastor of the church and in 1915 the Diocesan Administrator for the Ruthenian Greek-Catholic Church in the United States. Thus Newark became the official seat of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in the United States. Rev. Poniatishin undertook a key leadership role in the effort to convince the U.S. Government to recognize the nascent Ukrainian National Republic at the end of World War I.Buryk, Michael. “The United States and the Issue of Ukrainian Statehood, January 1918-December 1920”. pp. 394-399. He was also an important public figure in the local Newark community as well.

, which has numerous other images related to this parish ([archived site](https://web.archive.org/web/20240521154448/http://newarkreligion.com/photos/index.php?cat=80))](https://newarkreligion.com/photos/albums/userpics/10001/presruth01.jpg)

First Ruthenian Presbyterian/First Ukrainian Presbyterian Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Exterior, 1911. Photograph from https://newarkreligion.com/photos/index.php?cat=80, which has numerous other images related to this parish (archived site)

Unique to Newark was the establishment of a Protestant Ruthenian (later Ukrainian) church, the First Ruthenian Presbyterian Church of St. Peter and St. Paul. It was organized in June 1909 at 49/51 Beacon St, Newark, NJ. The pastor at the time was Rev. Volodymyr Pyndykowsky. Because of a 1907 dispute over the control of the St. John the Baptist Church property on Court Street and parish finances, a group of about 100 parishioners with the Rev. John Bodrug petitioned the Newark Presbytery to become a Presbyterian parish. They were formally accepted in 1909.The Newark Sunday Call. Newark, N.J. “Greek Church Case in Chancery”, July 10, 1908, p.2, “Mass is Now Celebrated in a Newark Presbyterian Church”, February 20, 1910, p.17, and “Mass and Prayers to Virgin in a Presbyterian Church”, March 10, 1912, Magazine Section, Part III, p.1. Kuropas, The Ukrainian Americans, pp. 70-71.

Rev. Vasyl Kuziw, the pastor of the Ukrainian Presbyterian parish from 1912-1917, was very active in both Ruthenian community and local public life and in 1913 was instrumental in initiating a program of Ukrainian studies at Bloomfield College which continued into the 1930’s. Bloomfield was a nearby suburb to Newark. Rev. Kuziw had arrived in the U.S. with his parents in 1904 coming from the village of Denysiv in Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine.Bykovskyi, Lev. Vasyl Kuziv. His life and activity. pp. 8-16. Throughout his life, he traveled extensively in Ukraine and was responsible for several humanitarian efforts to aid the population there. Kuropas, Myron B. The Ukrainian Americans: Roots and Aspirations 1884-1954. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1991. pp. 322-323. He also supported the establishment of a Ukrainian book section at the Newark Public Library, which was under the leadership of John Cotton Dana who was very supportive of the effort to establish a large foreign language book collection. Mr. Cotton Dana published a Ukrainian language advertisement in the local press in February 1914 to encourage the use of newly purchased Ukrainian books at the library.

In addition to Ukrainian Catholic and Presbyterian parishes, Newark also saw the establishment of a Ukrainian Orthodox Parish in 1918, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Holy Ascension (which moved to nearby Maplewood in 1974). In 1929, St. George Byzantine Catholic Church was organized at 26 Houston Street (and later stood at 208-214 Warwick St.). It is part of the Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Passaic, the Byzantine-Ruthenian Catholic Church, which serves the community of the Carpatho-Rusyns in the U.S.

Ukrainian Community and Public Life in Newark

“By the twentieth century, two-thirds of Newark’s population was foreign-born; census takers could identify more than 30 city neighborhoods with a predominant ethnic or racial group.”Malanga, Steve. “Philip Roth’s Newark”, City Journal. Spring, 2017. (https://www.city-journal.org/article/philip-roths-newark) And, Ukrainians were an integral part of this immigrant stew. By 1936 according to the Ukrainian National Association, the number of Ukrainians in Newark would grow to almost 7,000.Jubilee Book of the Ukrainian National Association, 1936, p. 614. Many lived in the old Third and Thirteenth Wards of the city (now part of the Central Ward).

Ukrainians (Ruthenians) developed a thriving community in the first decades of the 20th century in Newark. Some of their public events were covered in the local press. One stood out. On September 23, 1916 1,500 Ukrainians gathered in native dress including a division of Kozaks with the Boyan Choir singing on a float and paraded down Broad St. along with many other ethnic groups to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the founding of Newark.The Newark Sunday Call. Newark, N.J. “Picturesque Dresses Worn in Parade of Ruthenians”, September 25, 1916, p. 23. And, later that evening a concert was held at the local Metropolitan Theater dedicated to the Ukrainian writer and poet Ivan Franko. All of this was done under the auspices of St. John the Baptist Ukrainian Catholic Church.

The WPA “New Jersey Ethnological Survey”

During the later 1930’s, the Federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) conducted a survey of New Jersey ethnic groups through the New Jersey Writer’s Project. The New Jersey Ethnological Survey began its work in July 1938 under the direction of Charles W. Churchill and Vivian P. Mintz. Its focus was ethnic groups in Newark and nearby communities. A total of 14 ethnic groups were surveyed including Ukrainians. Documentation and records for this project are kept at the New Jersey State Archives in Trenton.New Jersey State Archives, Works Progress Administration (WPA), New Jersey Writers Project, New Jersey Ethnological Survey Records, 1935-1939, Box 5, Folders 13-28.

Basil Wheeler’s research and writeup about Ukrainians in Newark and nearby Irvington offers a detailed snapshot of the community primarily covering the period 1938-1939. There is a detailed list of 18 “Ukrainian leaders in Newark” which includes people like John Romanition and Stephan Shumeyko.

John Romanition (an anglicized spelling of the Ukrainian surname Romanyshyn) was a second-generation Ukrainian American who became a local attorney after graduating from the Law College of the University of Newark (which merged with Rutgers University in 1946 and was renamed the Rutgers University School of Law). Born in 1915 in Newark, Romanition would have a long career as an attorney in the Newark area, becoming assistant prosecutor of Essex County. He was also prominent in Ukrainian American affairs, serving two terms as president of the Ukrainian Youth League of North America (1937-1939). His father Paul, who arrived in the U.S. in 1909, was listed as one of the oldest Ukrainian residents of the Newark area community.

Stephan Shumeyko was another important Newark-born Ukrainian American community leader. He became the first editor of The Ukrainian Weekly when it was launched in 1933. He also organized the Ukrainian Youth League of North America and was its first president from 1933–1936. Mr. Shumeyko was also president of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America from 1944–1949 and was an author and translator.Encyclopedia of Ukraine, Vol. 4. University of Toronto Press, 1993. p. 685.

Wheeler’s research includes a long list of Ukrainian organizations active in Newark. It includes four churches and 30 organizations (including those headquartered in Newark and branches of organizations based outside of Newark). Of note is the American-Ukrainian Building and Loan Association founded in 1921. By 1931, its assets were $750,000 — equal to almost $14 million in today’s dollars. Another local Ukrainian American banking institution, Trident Savings and Loan Association, was established in 1922 and survived the Great Depression to reach assets of almost $18 million in the 1960’s.Encyclopedia of Ukraine, Vol. 3., p. 594.

Perth Amboy

Ruthenians began migrating to Perth Amboy in 1884 and to Carteret in 1896. Perth Amboy was settled in 1683 by Scottish colonists at the mouth of the Raritan River and was a capital of the Province of New Jersey from 1686 to 1776. Industrialization and immigration transformed Perth Amboy through the middle of the 19th century. Companies like A. Hall and Sons Terra Cotta, Guggenheim and Sons and the Copper Works Smelting Company provided jobs in factories for the residents’ ethnic neighborhoods such as “Budapest”, “Dublin”, and “Chickentown”, which were insular and very focused on their own immigrant groups.Wang, Paul W.; and Massopust, Katherine A. Perth Amboy. Arcadia Publishing, 2009. p. 19.

Religious and Ethnic Conflict among the Ruthenians

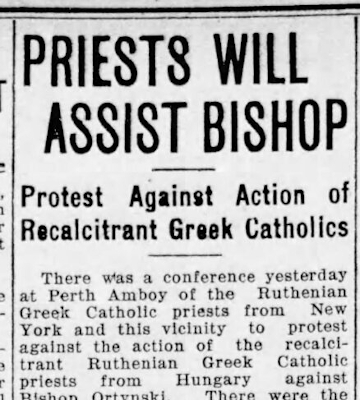

Perth Amboy Evening News (Perth Amboy, New Jersey), 1912-09-04

As happened in many of the newly established Ruthenian communities in the U.S., differences from the Old Country were magnified and led to major conflict in the New World. The first Ruthenians came to Perth Amboy from Transcarpathia (which was under the control of Hungary in the Austro-Hungarian Empire) around 1884. The Transcarpathians lived on the Western Slopes of the Carpathian Mountains and spoke a different dialect from the Galicians who lived on the Eastern Slopes of the Carpathians.Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church, 1908-1983. History of Ukrainians in Perth Amboy. Editor, Alexander Lushnycky, PhD. 1984. pp. 65. And so although the two Ruthenian groups initially were united in the parish of St. John the Baptist Church on Broad St. in 1896, they eventually separated by 1908 the Galician-Ruthenian group formed the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Ukrainian) Catholic Church.

The Composition of the Local Community

The Galician Ruthenians who arrived in Perth Amboy after the Transcapathians came from the regions of Sanok, Lisko, Peremyshl, Dobormil and Rohatyn. There was a large group from the village of Cherche (near Rohatyn). They comprised half of the parishioners of Assumption Church in its early days. The Cherche group were very pro-Ukrainian and this attitude put its mark on Assumption parish and the local Ruthenian community.History of Ukrainians in Perth Amboy. pp. 68-69.

The first Ruthenians in Perth Amboy resided along the railroad tracks in the northeastern section of the city. They worked in iron and steel works, factories producing roof shingles, and asphalt and other manufacturing companies. Some also found work on nearby farms. By 1910, Eastern Europeans had grown to sufficient numbers to warrant a discussion in the local press (The Perth Amboy Evening News) regarding whether additional categories should be in the Federal census and include the variety of Slavic people who were now in the U.S. (and it included Ruthenians).

Ukrainian Dramatic Club of Perth Amboy

State Street became an important community hub, with its Ukrainian Hall and picnic grounds at number 762. The local press (The Perth Amboy Evening News) provided good coverage of activities and events in the local community calling the residents “Ruthenians” early on and “Ukrainians” beginning in the 1920s. By the middle of the 1930s, there were 460 families (a total of 3,000 people) active in 15 organizations, including a “American-Ukrainian Democratic Club” with its own “People’s Club”. The house, worth $15,000, housed almost all Ukrainian societies and a library.”Jubilee Book of the Ukrainian National Association, 1936, p. 618.

Ukrainians opened many businesses that served the local community. In 1936, there were 21 Ukrainian enterprises: 4 grocery stores, 6 hotels, 2 barber shops, 1 tailor, 1 dyer, 2 builders, 2 undertakers and 3 transport companies. Ukrainian professionals included one lawyer, three pharmacists, two music teachers, and one public school teacher. Thirteen Ukrainians worked in Perth Amboy City jobs.Jubilee Book of the Ukrainian National Association, 1936, p. 618.

Carteret

A separate Ruthenian/Ukrainian community grew in Carteret, a nearby suburb of Perth Amboy. Carteret and Chrome village were part of Woodbridge Township in Middlesex County until 1906, when they became the Borough of Roosevelt. In 1922 the name was changed to the Borough of Carteret.

In the 1880’s, Canada Manufacturing, Williams & Clark Fertilizers and Wheeler Condensers bought property on the Staten Island Sound and sparked the industrialization of the village of Carteret. In 1905, Chrome Steel, Liebig Mfg., and U.S. Metals and Refining became a source of new jobs for an ever-growing population.

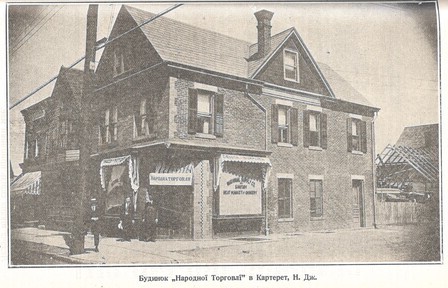

The ‘Narodna Torhovlia’ building in Carteret, N. J.

The first Ruthenians arrived in Carteret in 1896 and came from these counties in Ukraine: Syanik, Dobromyl, Zolochiv, Zbarazh and Rohatyn. They worked in factories of metal products, oil refineries, factories of artificial fertilizers, paints and tailoring workshops. Various societies and organizations were formed, including a branch of the Ukrainian National Association, the Society of the Zaporozhye Sich, founded in 1912 for which the present author Michael Buryk’s great uncle Mykhailo Cherpanyak (Czerepaniak) was the chairman.Jubilee Book of the Ukrainian National Association, 1936, p. 618.

![Dedicate Ch. At Roosevelt -- St. Demetrus [sic] Ruthenian Greek Catholic Edifice](/ukrainians-in-nj/objects/thumbs/perth_amboy_evening_news_1911_09_25_5_th.jpg)

Perth Amboy Evening News (Perth Amboy, New Jersey), 1911-09-25

In 1910, St. Demetrius Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church was founded by about 30 families from Halychyna. A church building was erected in 1911 and blessed by Ukrainian Catholic Bishop Soter Ortynsky. The parish continued to grow with the arrival of new immigrants. In 1927, a majority of the parish voted and decided to leave the Greek Catholic diocese and to join the Ukrainian Orthodox Church under the jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople. In 1931, Father Joseph Zuk became the pastor and was consecrated their bishop and the church became St. Demetrius Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral.

Not all the parishioners of St. Demetrius were satisfied with this decision. Under the leadership of Joseph K. Ginda, who had been one of the founders of the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Perth Amboy and of St. Demetrius in Carteret, some of the former parishioners of St. Demetrius would eventually establish St. Mary’s Ukrainian Catholic Church in Carteret in 1949. By 1936 there were 2,000 Ukrainians in Carteret. Of this total, 1,467 were parishioners of St. Demetrius Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral.

The Passaic Area

The city of Passaic and the surrounding communities were a magnet for immigrants in the early part of the 20th century. By 1910, more than 50% of the city’s population of 54,773 inhabitants was foreign-born and this was the largest proportion of any U.S. city at the time.Ebner, Michael H. “Passaic, New Jersey, 1855-1912 : City-building in Post-Civil War America”. Doctoral dissertation, Corcoran Department of History, University of Virginia, 1974.

The production of textiles and other types of manufacturing provided a constant source of jobs, including companies like the Botany Worsted Wool Mills, the Okonite Cable Company, the Manhattan Rubber plant and others.History of Ukrainians in Perth Amboy. pp. 79 Nearby Clifton was an agricultural hub which offered additional opportunities for new immigrant employment.

The first Ruthenian immigrants and their differences

The first Ruthenian immigrants began to arrive from Transcarpathia (Zakarpattia) and Lemkivshchyna in 1885 and in 1895 a group of 80 arrived from Eastern Galicia.Jubilee Book of the Ukrainian National Association, 1936, p. 617. Hungarians, Slovaks, Poles and other Eastern Europeans also came and established their own communities.

As had happened in other places where Ruthenians settled in the U.S., religious conflicts developed because of differences that existed in the Old Country. Zakarpattia was under the control of Hungary in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and there was a strong Hungarian influence over all aspects of life there including religion. There was a segment of the Lemko population who, although they were Greek Catholic, over time developed an orientation towards Russia and Russian Orthodoxy. The Ruthenians from Eastern Galicia (Halychany) became strongly pro-Ukrainian as this new identity developed in the early 20th century.

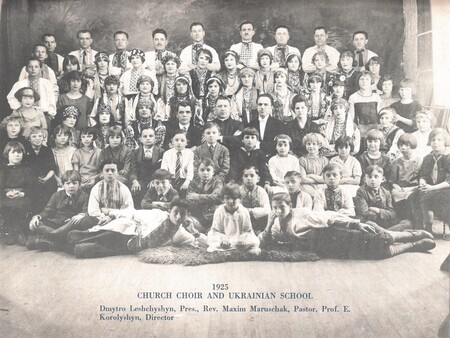

Church choir and Ukrainian school, Holy Ascension Ukrainian Orthodox parish (Passaic)

By 1903, there were three churches that Ruthenians attended: St. Michael’s Greek Rite Catholic Church (the parish began in the 1890’s and the church constructed from 1902-1905); Sts. Peter and Paul Orthodox Catholic Church (1902); and, St. Stephen’s Catholic Church (a Hungarian parish, 1903). With the selection of Rev. Soter Ortynsky as the first Ukrainian Greek Catholic bishop in the U.S. in 1907, a movement began among those Galician-Ruthenians who were pro-Ukrainian to establish their own parish. And so St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Church was established in 1910. Michael Tabachuk (who arrived from Galicia in 1907) was one of the founders of the church.Jubilee Book of St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Church, pps. 80-81. One of the first full-time Ukrainian day schools in New Jersey was established in the parish in 1922. A Ukrainian Orthodox church, Holy Ascension Ukrainian Orthodox Church, was founded on Hope St. in Passaic in 1925. The church later moved to Clifton in the late 1960’s.

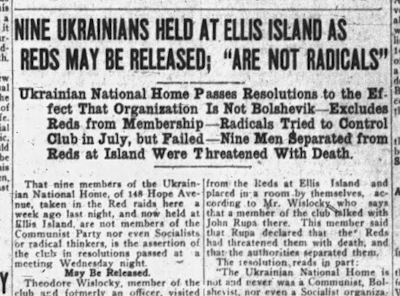

Ukrainians and the “Red Scare” of 1920

Passaic Daily News, January 10, 1920.

While the army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic was fighting to secure an independent, non-Communist Ukraine, the Passaic Ukrainian community was swept up in the national Red Scare of 1917-1920. On January 3, 1920 the Passaic Daily News reported that 16 men from the Ukrainian Socialist Club on Third St. and 8 from the Ukrainian National Home on Hope St. were arrested with “Communist literature”. They were part of a national round-up of 4,500 alleged members of the Communist and Communist Labor parties. Those arrested in Passaic were sent to Ellis Island for detainment and eventual deportation. The eight men arrested at the Ukrainian National Home were exonerated in late February and released.Passaic Daily News. Passaic, N.J. “64 Reds are Caught Here”, January 3, 1920, p. 1. The Paterson Morning Call. Paterson, N.J. 1920. “Release Eight Passaic Men”, February 27, 1920, p. 7. No information was published about the detainees from the Ukrainian Socialist Club.

1921 “Tag Day” and other activities

Passaic Daily News (Passaic, New Jersey), 1921-04-15

Passaic Mayor John McGuire and the Ukrainian Relief Committee of Passaic held a Ukrainian “Tag Day” on April 16, 1921 to raise funds for the children of war-torn Eastern Galicia. Rev. Leo Lewicky, pastor of St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Church, participated in this effort.

Local Ukrainians showed their American patriotism by forming a League of American Citizens of Ukrainian Extraction in July 1922 in the auditorium of the new Ukrainian American school established by St. Nicholas Church. The Very Rev. Lewicky spoke at the event attended by 50 parishioners.

Several hundred people attended a mass meeting on March 23, 1923 at St. Nicholas Church hall where the Very Rev. Leo Lewicky spoke about the decision of the conference of ambassadors which granted East Galicia to Poland on March 14, 1923. After the meeting a letter was sent to President Harding and Secretary of State Hughes to protest the decision.Passaic Daily News. “Ukrainians Here Send Protest to President Harding”, March 26, 1923, p. 1.

Throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s the local press continued to report regularly on the many social, cultural and political activities of the Passaic area Ukrainian community. By 1936, there were 2,000 Ukrainians around Passaic, Clifton, Garfield, Lodi, Wallington, Rutherford, Athenia, Singac, Little Falls, and Carlstadt. The community was very active at this time, with 7 Ukrainian aid societies and 8 Brotherhoods, Sisterhoods, youth organizations, and choirs.Jubilee Book of the Ukrainian National Association, 1936, p. 617.

Hillside (Union County)

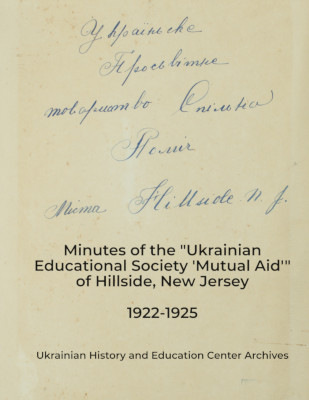

Hillside in the 1920s would still have been a relatively bucolic suburb of Newark, having only been incorporated as a township in 1913. There were Ukrainian Americans living there, but they did not seem to leave a paper trail in the English-language press and there were no Ukrainian parishes founded there prior to World War II. However, there is one major primary source documenting this community: a book of handwritten minutes from 1922 to 1925 of an organization that called itself the “Ukrainian Educational Society ‘Mutual Aid’” which is in the archives of the Ukrainian History and Education Center.

Meeting minutes of the Ukrainian Educational Society ‘Mutual Aid’ in Hillside, New Jersey

These minutes provide an interesting, albeit schematic and at times cryptic, view of the internal workings of a Ukrainian American organization in the 1920s. The society in question, unlike the massive Ukrainian National Association, was hyper-local to the Hillside area. However, its ambitions were large: within months of their formation they had purchased property with the goal of building a school and community center. We don’t know the exact address of the property, but the minutes of their February 18, 1923 meeting state that they were looking at lots “на Hardford [sic] ave коло Boloy [sic] st.”, presumably meaning “on Harvard Ave. near Bloy St.” There is nothing in the minutes about actual construction of any building. However, later entries do talk about a school for children and social and amateur theatrical events for adults.

Curiously, the society’s members refer to each other in the minutes as “tovarysh”, which can be translated as “friend”, “fellow”, or “comrade” and (as is well-known) was the preferred form of address among Communists. However, it is extremely unlikely that’s what they were, as the very first activity they undertook after their organizational meeting on New Years Eve (December 31, 1922) was to go Christmas caroling. Caroling was a very common form of fund raising for Ukrainian American parishes and organizations for much of the 20th century, but it’s probably not something that any self-respecting Marxist would be caught doing. It’s more likely that “tovarysh” came from the fact that the organization was a “society” or “fellowship” (“tovarystvo”, which comes from the same root as “tovarysh” and could be literally translated as “group of friends”). In fact, they apparently had a nontrivial discussion in that very first meeting about whether their organization should be a “tovarystvo” or a “kruzhok” (“circle”), finally settling on the former. It may have simply been natural for them to refer to a fellow member of the “tovarystvo” as a “tovarysh”. It is possible that they were socialists of some form, though the minutes do not contain anything that would shed light on their political leanings.

They were, however, very adamant about not being connected to or associated with any religious organization. When a delegation “of church representatives from Newark” (likely from St. John the Baptist parish) came to their meeting on July 22, 1923 to propose an educational collaboration, they were sent away with the message that “наше товариство і наш статут нимає і ниможе мати нїчого спільного з церквами і жадної роботи разом ниможим робити” (“our society and our bylaws do not and cannot have anything connected with churches and we cannot do any kind of work together”). It’s also intriguing that a proposal was raised at one of their early meetings (Feb. 4, 1923) to allow women to join as members, but that discussion was tabled “until the appropriate time”, which apparently never came.

Despite their initial momentum, by 1924 they seemed to be running out of steam. Already in December 1923, their president was exhorting the membership to come to meetings more frequently and to put more effort into the organization. By late 1924, they were running into serious financial difficulties and were having problems affording to heat the school and pay the teacher. It seems that they did not survive beyond 1925. Hillside would go on to have other Ukrainian American organizations, and a Greek Catholic parish would be founded there in 1957. It still exists and is located, interestingly, on the corner of Liberty Ave. and Bloy St., about five blocks away from the property purchased by the “Ukrainian Educational Society ‘Mutual Aid’” in 1923.