Mike Gburyk, the paternal grandfather and namesake of the present author, was only married six months when he arrived at Ellis Island in June 1911 on his way to meet his brother-in-law Michael Czerepaniak in Carteret, N.J. His native village of Siemuszowa near Sanok (Ukr. Sianok or Sianik) seemed very far away. He soon became one of more than 470,000 Ukrainians (or Ruthenians, as they would have been called then) and their descendants living in the United States.This is the estimate of the number of Ruthenians/Ukrainians living in the U.S. in 1909. It was made by the author Julian Bachinskyi in his extensive work on Ukrainian immigration in the U.S. published in L’viv in 1914, The Ukrainian Immigration in the United States. See Kuropas, Myron B. The Ukrainian Americans: Roots and Aspirations 1884-1954. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1991. Pp. 24-25.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ruthenian/Ukrainian immigrants took the long journey from the severely impoverished province of Galicia in Austria-Hungary seeking a better life in America, or at least to earn enough money to return home richer. Agents for the coal companies, railroads and steamship lines were crisscrossing Galicia at the time and encouraging able-bodied men to emigrate to America to help build the dynamic industrial engine that was taking shape.

Since Michael Czerepaniak was already there and doing well as a local businessman (he had experience managing the grain mill for the local nobleman back in Siemuszowa), it was natural for Mike Gburyk to end up in New Jersey. Like many of his fellow countrymen who were living in the area, he found work in the Benjamin Moore Paint Company and later in the steelworks nearby. His wife Julia arrived in 1913. Carteret was not Gburyk’s final stop, however. By the early 1920s, he, Julia, and their young family had enough of factories and urban life and they moved to Minersville, Pa., in the anthracite (hard coal) region where many Ruthenians were already established.

Statistics and Early Settlement

Beginning in the 1870s and continuing until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Ruthenians/Ukrainians began to come to the U.S. in increasing numbers. At first, most came from the Subcarpathian region of Galicia and the Lemko Region of current southeastern Poland. Later, they came from eastern Galicia and Bukovyna in Austria-Hungary, and eastern Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire.

The U.S. did not start counting Ruthenians as a separate immigrant group until 1899. According to the Annual Reports of the U.S. Commissioner General of Immigration, 268,311 Ruthenian immigrants arrived in the United States between 1899 and 1930.Halich, Wasil. Ukrainians in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1937. Appendix A, pp. 152-153. The vast majority (87%) settled in Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey. The total arrivals in New Jersey during this period was 29,830. These numbers, however, do not include immigrants who might have been counted as Russians, Poles, Hungarians, or under other ethnic classifications.

According to U.S. immigration records, about 50% of Ukrainian immigrants were illiterate when they arrived. Since they had no technical skills, most were forced to find work as unskilled laborers.Halich, Ukrainians in the United States, p. 27. The coal mines of Pennsylvania were the first choice for many, but others decided to remain in New Jersey in major manufacturing and industrial centers. A smaller number, however, eventually became agricultural workers and farmers in the Garden State.

Among the early communities established by Ukrainians in New Jersey during the first wave of mass immigration were Jersey City (1880); Perth Amboy (1884); Passaic area (1885); Elizabeth (1895); Carteret (1896); Trenton (1897); Bayonne, Newark and New Brunswick (all around 1899); Raritan (1905); Great Meadows, Linden and Roselle (1906); Bridgeton and Oxford (1907); Whippany (1908); Millville and Bound Brook (about 1910). Additional settlements were later formed in Manville and Williamstown (1912); Paterson (1913); the Plainfields (1920s); Iselin (1924); Piscataway-New Market “Nova Ukraina” (1927); Irvington and Maplewood (1930’s).Rak, Dora. “Ukrainians in New Jersey from the First Settlement to the Centennial Anniversary”. In The New Jersey Ethnic Experience, edited by Barbara Cunningham. Wm. H. Wise & Co., Union City, N.J., 1977. p. 441.

Early Community and Civic Life

Although most Ukrainian immigrants had no formal education, they certainly had intelligence and the ability for social organization. Their Greek Catholic religion (very few of the first immigrants were Orthodox) offered them an opportunity to establish churches wherever they settled. In 1884 at the request of Ruthenians living in Shenandoah, Pa., the Greek Catholic priest Fr. Ivan Wolansky (1857-1936) arrived in New York and headed directly to this coal country town. There the first Ukrainian Catholic Church in the U.S. would be built in 1886. Fr. Wolansky then began organizing church committees in other Ruthenian communities around the U.S. including in Jersey City.Kuropas, The Ukrainian Americans, pp. 40-43. Under his guidance, the Jersey City Greek Catholic parish of Sts. Peter and Paul was formed in 1887 and a small chapel built at the corner of Henry St. and Chestnut Ave. on the hill overlooking the old Jersey City cemetery on Newark Ave. In 1891, a wooden church was built on the same spot. Eventually the parish built a brick church in 1902 at the corner of Sussex and Greene Sts. in the Paulus Hook section of downtown where most of the Ukrainians lived.

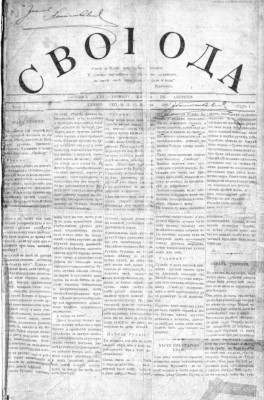

Front page of the first issue of ‘Svoboda’

Since there were no intellectuals among the earliest immigrants, priests served as spiritual, social and cultural leaders. In early 1889, Fr. Hryhorij (Gregory) Hrushka (1859-1913) arrived in the U.S. He spent a short time in Olyphant, Pa., but eventually settled in Jersey City as the pastor of Sts. Peter and Paul Church. One of his accomplishments was establishing a Ukrainian cooperative store (“The Ukrainian Trade Market”) on Morris St. in 1890. He is probably best known for founding Svoboda (Freedom) in 1893 as the first Ukrainian language newspaper in the U.S. Lutwiniak, Theodore. “Ukrainians Active Here Since 1879”. The Jersey Journal, Jersey City, New Jersey, May 2, 1942, p. 103. Svoboda, (currently the oldest continuously-published Ukrainian newspaper in the world) and its English language companion newspaper The Ukrainian Weekly (established in 1933), became an essential part of the Ukrainian American community offering the immigrants and their descendants a written channel to exchange information about what was happening in the U.S. as well as back in the old country.

Slavic immigrants had begun to organize themselves for mutual benefit in fraternal associations, and Ruthenians started to join them. In 1894, four Galician priests (Revs. Konstankevych, Obushkevych, Poliansky and Hrushka) met in Jersey City to discuss the formation of a new Ruthenian fraternal group, the “Ruskyi Narodnyi Soiuz” (“Russian National Union”), with the intention of promoting it in Svoboda. The organization’s name went through various iterations until it finally became the “Ukrainian National Association” in 1914 with its headquarters in Jersey City, located at 81-83 Grand St. The organization grew to become an important part of Ukrainian American civic, educational and cultural community life.Kuropas, The Ukrainian Americans, pp. 74-76.

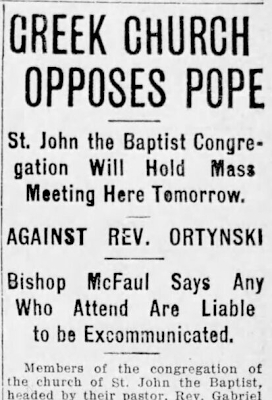

It is important to note here that there were ethnic and religious conflicts among the early Slavic immigrants. Poles were the older immigrants and overwhelmingly Roman Catholic while Ruthenians were Greek Catholic (and sometimes Orthodox). In Galicia, Poles had played a significant role in the government and land ownership, which often clashed with the Ruthenian population of Eastern Galicia.Balch, Emily Greene, Our Slavic Fellow Citizens. Charities Publication Committee, New York, 1910. pp. 120-131. This conflict continued in the United States.

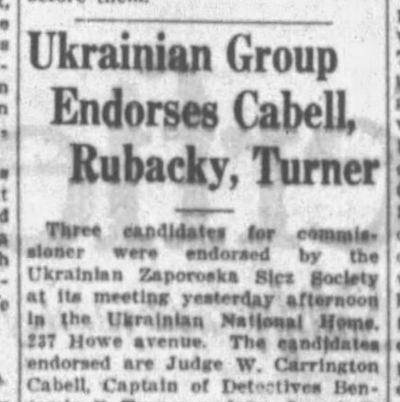

Perth Amboy Evening News (Perth Amboy, New Jersey), 1912-08-16

Ruthenians were also in conflict among themselves. The group of Ruthenians under discussion in this article eventually identified as Ukrainians. Others had an orientation toward the Russian Empire and were known as “Moscophiles” or “Russophiles” and often identified as Carpatho-Rusyns and attended Russian Orthodox parishes. A third group preferred to call themselves simply “Rusyns”, which is what they had called themselves in Galicia. In Jersey City, the early Ruthenian community experienced a split when some members of the Greek Catholic parish of Sts. Peter and Paul left to create the Russian Orthodox parish of Sts. Peter and Paul on Grand Street in 1907. In 1915, 24 Ruthenian families in the Lafayette section of Jersey City formed their own church which eventually became known as St. Mary’s Byzantine Catholic Church. This separation among Ruthenians immigrants played out in other New Jersey communities and throughout the United States.Kuropas, The Ukrainian Americans, pp. 33-72.

Expansion Beyond Jersey City

While Jersey City in Hudson County was the initial hub of the Ukrainian American community in New Jersey, immigrants began to settle in numbers in the urban areas of Passaic, Essex, Middlesex, Morris, Union, Somerset and Mercer Counties, and eventually even to rural areas like Warren and Cumberland Counties.

The Perth Amboy-Carteret area from around 1884-1886 had many Ukrainian immigrants drawn to work in manufacturing, metal working, steel production and other industrial occupations.Jubilee Book of the Ukrainian National Association in Commemoration of the Fortieth Anniversary of Its Existence. Svoboda Press, Jersey City, N.J., 1936. pp. 591-622. Contains a list of all the Ukrainian communities in New Jersey at the time of publication with historical background and other useful information. The Ukrainian Catholic parish of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary was formed here in 1908 by immigrants from the Galician counties of Rohatyn, Peremyshl, Dorbromil, Sanok, Horlyc and Lisko. Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church, 1908-1983. History of Ukrainians in Perth Amboy. Editor, Alexander Lushnycky, PhD. 1984. pp. 39-70. A group of strongly Ukrainian-identifying residents of the village of Cherche near the town of Rohatyn emigrated to Perth Amboy and were very actively involved in the establishment of the church as well as local civic life. They encouraged their fellow countrymen to emigrate here.

Not all Ukrainians during the first wave of mass immigration settled in urban areas. Some went to smaller cities like Elizabeth, and continued westward to rural New Jersey. In 1906, the brothers Roman and Ivan Kowalik arrived in the farming community of Great Meadows. It was known for its lush meadows and beautiful countryside. The soil here is made up of a rich fertile black compost that makes it most suitable for growing vegetable crops of all types, especially root crops. The brothers were followed by other Ukrainians from Radekhiv and Zalishchyky areas of Galicia. They became farm workers and eventually acquired their own land. They built the Ukrainian Catholic Church of St. Nicholas in 1923. Jubilee Book of the Ukrainian National Association, 1936, p. 599; Halich, Wasyl. Ukrainians in the United States. p. 49.

Advertisement in ‘Svoboda’ promoting real estate in Millville

In Cumberland county of southern New Jersey, a colony of Ukrainians developed in Millville after 1910 as a result of glowing advertisements in the Svoboda newspaper placed by the real estate agent Wasyl Metolych. About two hundred families settled there and developed a local community of homes, farms, schools, and two churches. Many become disenchanted with their small strip landholdings of 10-20 acres, saying the advertisements had misrepresented the actual local conditions for agriculture, as the sandy soil was very different from the black earth found in other areas like Great Meadows. But Ukrainians continued to come from other urban areas in New Jersey, and even from as far away as North Dakota and Galicia. Eventually the residents were able to make a go of it as truck farmers.

World War I and Ukraine’s Drive for Independence

Passaic Daily Herald (Passaic, New Jersey), 1927-04-11

From 1914 to 1939 (known as “The Second Wave”), Ukrainian immigration slowed to a trickle. Of the approximately 10,000 who arrived in the United States during that period, about 500 became residents of New Jersey. Rak, Dora. “Ukrainians in New Jersey from the First Settlement to the Centennial Anniversary”. p. 438. The tumultuous years of World War I and the Immigration Act of 1924 combined to impede the immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans. Although the Ukrainian American community in New Jersey was no longer growing as quickly in numbers as it had before World War I, its political influence was increasing. Not only were they becoming involved in American politics by organizing clubs associated with American political parties and throwing support behind particular local candidates, they were also engaging in activism, advocacy, and lobbying on behalf of Ukrainians in what by then was the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union.

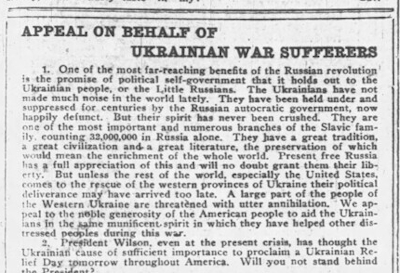

Passaic Daily News (Passaic, New Jersey), 1917-04-20

In 1917, New Jersey Ukrainians made a significant contribution to raising public awareness of Ukraine. Major famine and extensive destruction in their homeland from years of war prompted an effort by Ukrainian political organizations to make Americans more cognizant of the dire situation. The Ukrainian National Committee was established in the fall of 1916 in the U.S. to aid victims of the World War in Ukraine. Because there were many Ukrainian Americans in his district, Congressman James Hamill of Jersey City introduced a resolution in January 1917 that was adopted by Congress in February that led to President Woodrow Wilson proclaiming April 17, 1917 as “Ukrainian Day”. As a result of this, a large amount of money was raised from public collections for a Ukrainian relief effort. And, this was the first time that the word “Ukrainian” appeared in the Congressional Record.

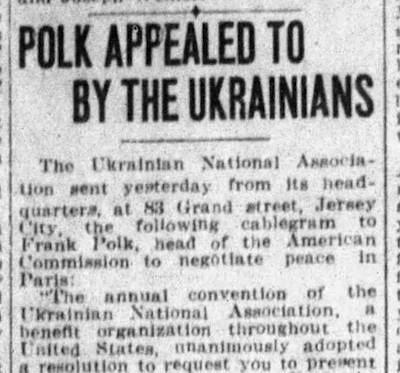

Hudson Observer (Hoboken, New Jersey), 1919-11-01

In the next few years, Congressman Hamill would continue to actively support Ukrainian Americans and especially his own constituents in their efforts to gain recognition of an independent Ukrainian state. Although he was never successful in this work, he served as an important liaison between Ukrainian Americans and the American government. Buryk, Michael. “The United States and the Issue of Ukrainian Statehood, January 1918-December 1920”. pp. 394-399. In Dushnyck , Walter, and Chirovsky, Nicholas L. Fr., editors. The Ukrainian Heritage in America. New York: Ukrainian Congress Committee of America, 1991. Two other prominent New Jersey officials, U.S. Senator Joseph Frelinghuysen and President Wilson’s secretary Joseph Tumulty also assisted Ukrainians in their humanitarian and lobbying efforts.

New Jersey Ukrainians were very patriotic and took part in government efforts to finance the U.S. participation in World War I and the Allied war effort in Europe through war bonds (“Liberty Loan Bonds”). The Ukrainian National Home in Jersey City bought $28,000 of these bonds (worth almost $500,000 in 2024 dollars), as reported by the Jersey Journal in June 1919. The Home was also active in encouraging local Ukrainian immigrants to become U.S. citizens “The Jersey Journal”, Jersey City, New Jersey. June 4, 1919, p.6. .

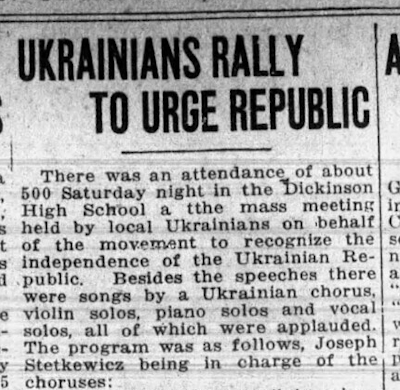

Hudson Observer (Hoboken, New Jersey), 1919-11-24

During this time and into the 1920’s, there were many public events held to rally the community and all Americans to the cause of a free and independent Ukraine. These events took place in various cities in New Jersey where Ukrainians had settled including Jersey City, Perth Amboy and Trenton. Local parish priests like Fr. Alexander Ulitsky in Jersey City and Fr. Joseph Chaplinsky (Czaplinsky) in Perth Amboy played a major role in organizing these rallies. In general, the local press was sympathetic to the cause of the Ukrainians.

Cultural Life and Education

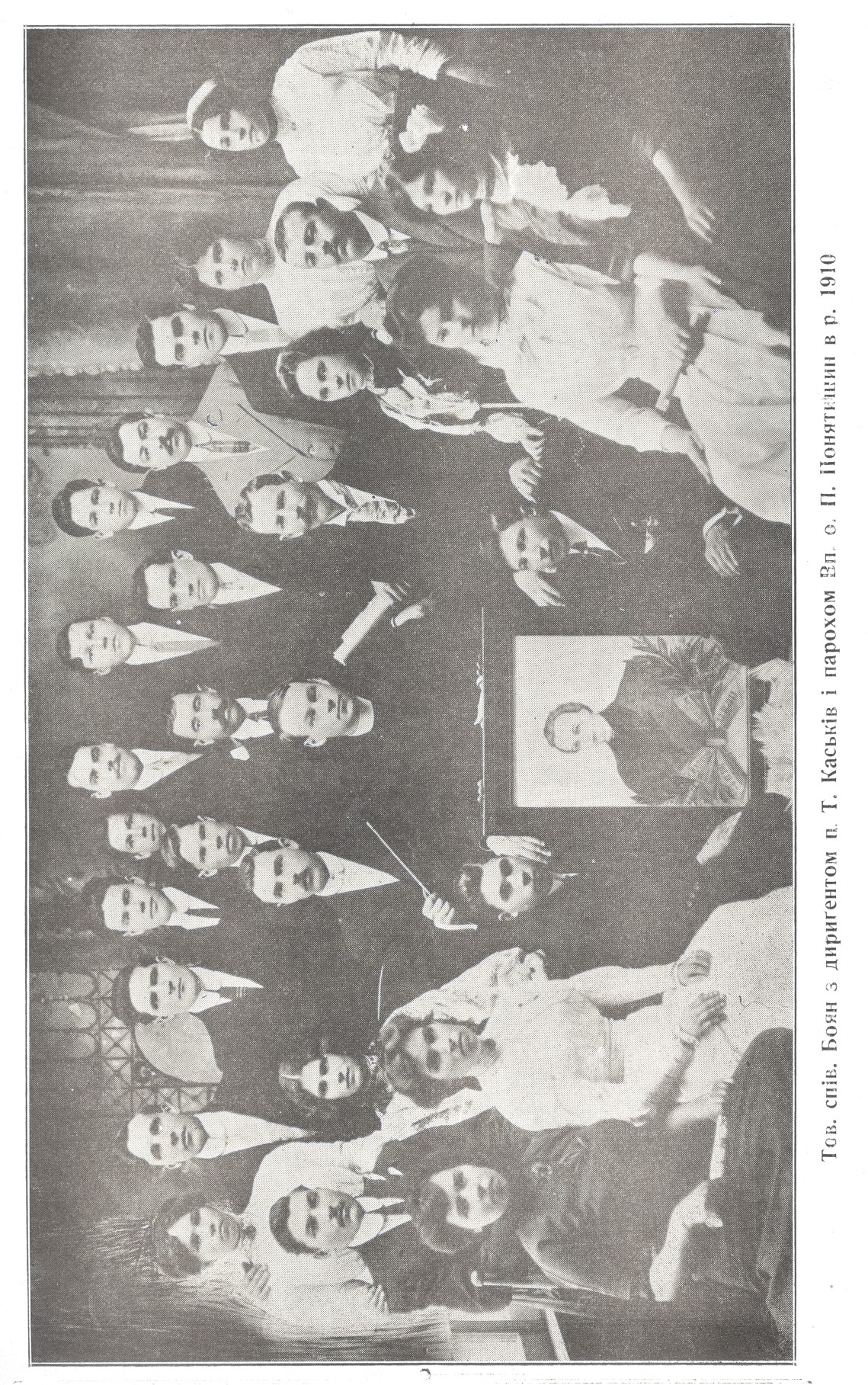

By the 1920’s and into the 1930’s, New Jersey Ukrainians had developed a wide range of cultural offerings. Choirs, dance groups and drama troupes were common.

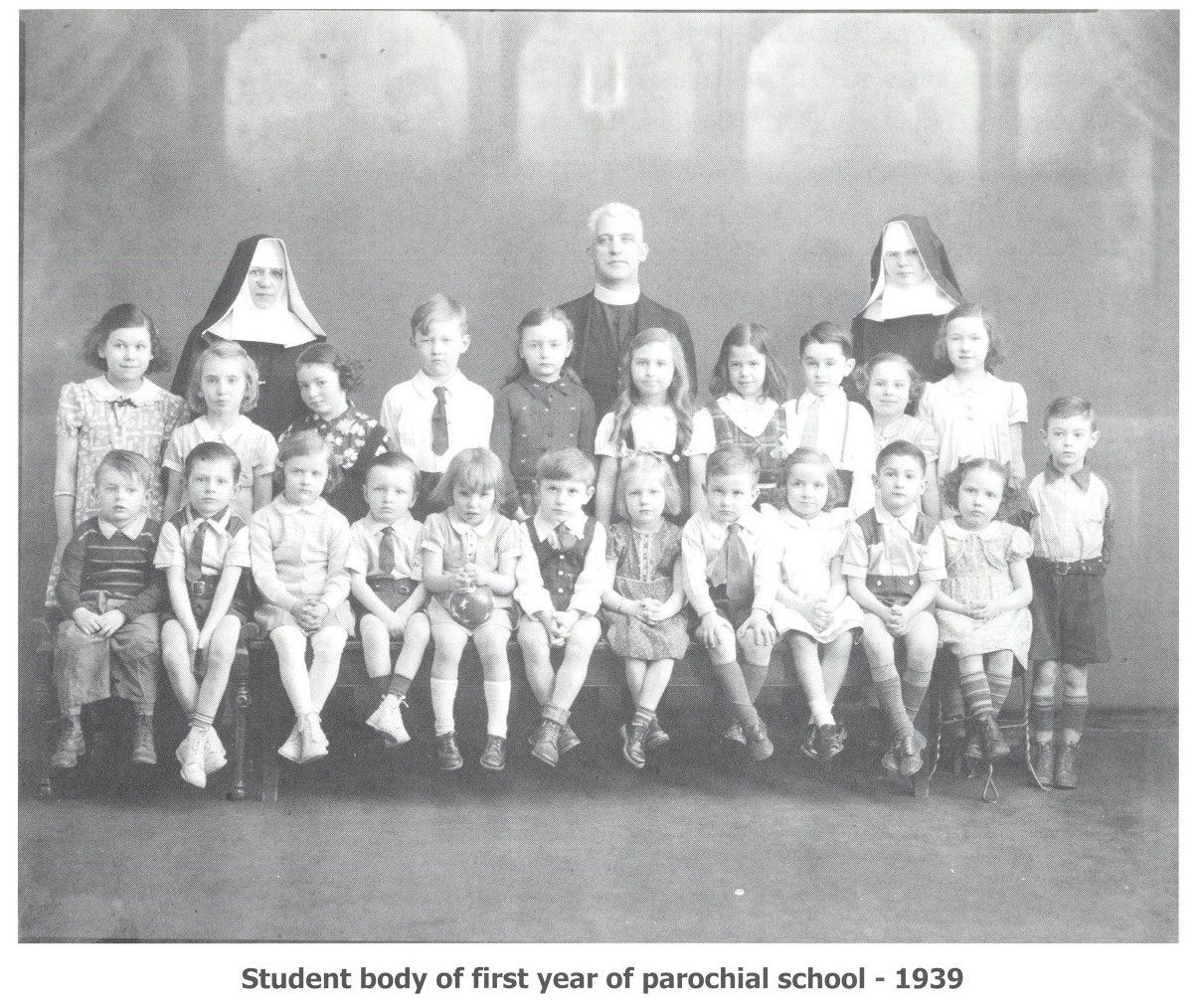

Most communities had heritage schools that taught Ukrainian language and history to the younger generation. Many of these programs met in church basements. However, in the fall of 1921, the parish of St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Church in Passaic broke ground for its own school building and hall that was completed in 1922 and still stands today. Initially, it was only an evening school because many children worked during the day at nearby factories, but by 1940 it became a regular parochial day school which continues to today. Jubilee Book of St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Church, Passaic, N.J. 2010. pps. 109-110. “Dedicate New School of the Ukrainian Catholic Church”, Passaic Daily News, Passaic, N.J., May 31, 1922, p.1 In 1939, St. John the Baptist Ukrainian Catholic Church in Newark opened its own full-time parochial day school with approximately 20 pupils. It continued to grow and by the 1950’s had 486 pupils.

Newark and nearby Bloomfield were important educational centers for local Ukrainian Americans. Beginning in 1913 Bloomfield College and Theological Seminary had courses in Ukrainian (Ruthenian) language, literature and history. The Ukrainian American college professor and author Wasyl Halich studied here from 1915-1918. He was a pioneer in the study of Ukrainians in America and wrote the 1937 book “Ukrainians in the United States” Halich, Wasyl. The Americanization of a Ukrainian boy, 1975.

The Rev. Basil Kusiw (Kuziv), pastor of the First Ukrainian (Ruthenian) Presbyterian Church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Newark, was the head of the Ukrainian department and the founder of this program at Bloomfield College. He was also instrumental in raising funds to donate Ukrainian books to the Newark Public Library, which developed a special section for Ukrainian publications at the time Bykovskyi, Lev. Vasyl Kuziv. His Life and Activities (in Ukrainian). Detroit, 1966. Ukrainian Evangelical Association in North America. p.15 and p.17. This was done in conjunction with the efforts of Newark Public Library director John Cotton Dana, who encouraged the establishment of foreign language collections for the use of the local immigrant communities.

Announcements of public cultural performances were found in the local press and reports about them were complimentary. In 1933, the Svoboda newspaper launched a major effort to reach out to the second generation of Ukrainian Americans by publishing an English language companion newspaper, “The Ukrainian Weekly”. Jersey City was the home office for this new publication that has become an important voice of the Ukrainian community in the United States.

Athletics and Sports

In addition to education, culture, and activism, athletics and sports played a role in the life of Ukrainian Americans in New Jersey. In the early years, it was focused not primarily on competitive sports, but on what would have been called “physical culture”, such as gymnastics, strength training, and similar activities, often in organized groups. Such physical culture organizations were popular in eastern Europe, including the Czech, Polish, Slovak, and later Ukrainian “Sokol” (“Falcon”) organizations. In Ukraine, one of the groups in this wider movement was called the “Sich”, named after a term for Cossack fortifications. It was founded in 1900 in Zavillia, Sniatyn region, then spread to other locales. A unified regional organizational structure was established in 1908, with its leadership dominated by members of the Ukrainian Radical Party. From the beginning, local Sich organizations had a strong component of Ukrainian ethnic identity, while remaining focused on athletic activities and serving as volunteer fire brigades.

By 1915, the Sich had made the leap across the Atlantic, starting with a branch in New York City. During and after the ill-fated period of Ukrainian independence that began in 1917, the Sich took on more paramilitary overtones, with military-style uniforms and marching drills. In the mid-1920s, the U. S. Sich leadership became more political and openly professed support for the conservative Pavlo Skoropadsky, the would-be Ukrainian monarch. But it’s not clear how much the rank-and-file membership would have cared about this.

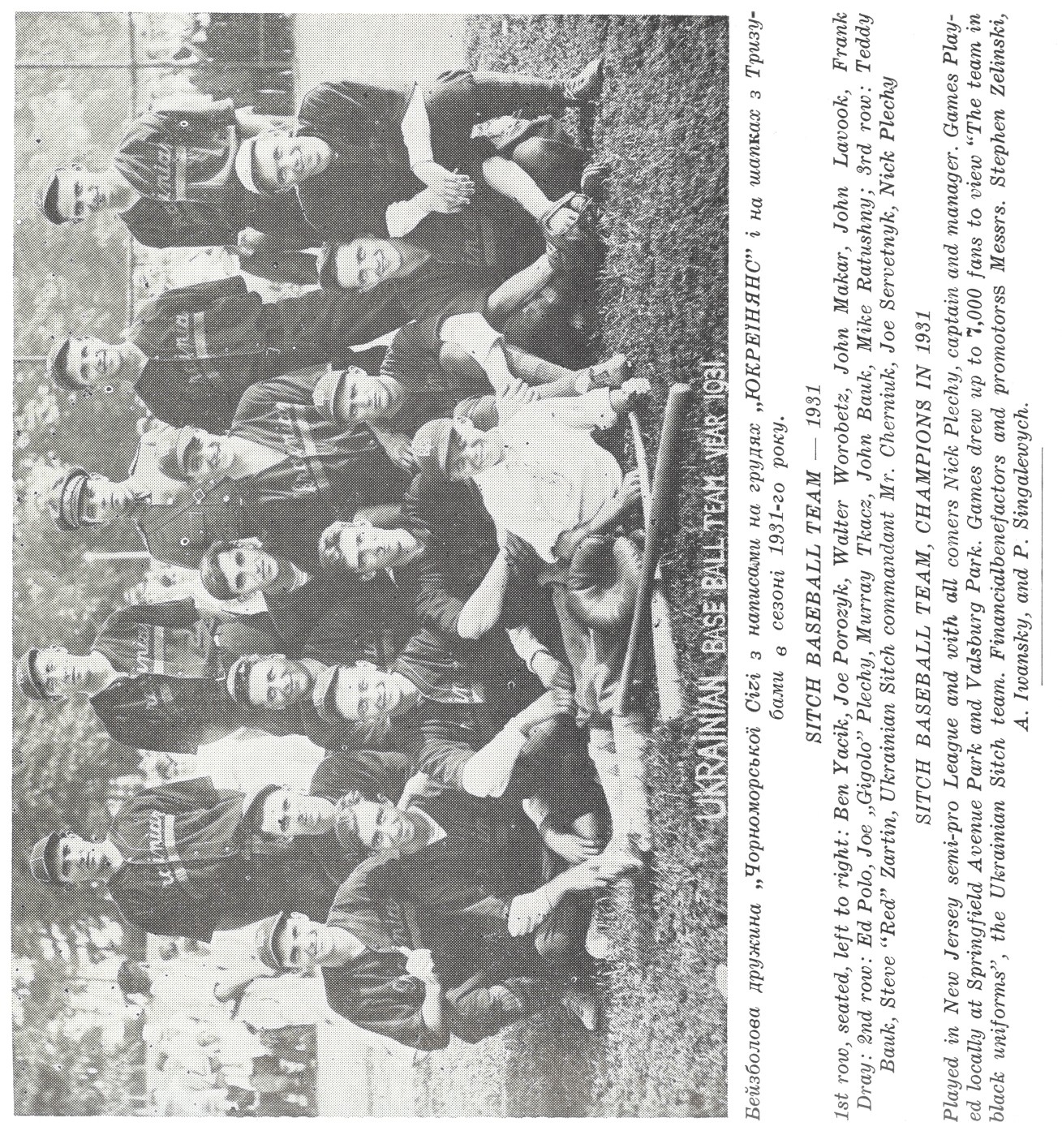

In 1924, a Sich or Sich-inspired group called the “Chornomorska Sich” (“Black Sea Sich”) was formed in Newark, later known in English as the “Newark Ukrainian Sich”. At first, they were very much within the uniformed, quasi-military Sich zeitgeist of the time, but by the early 1930s they were also fielding a semi-pro baseball team called the “Ukrainians”.

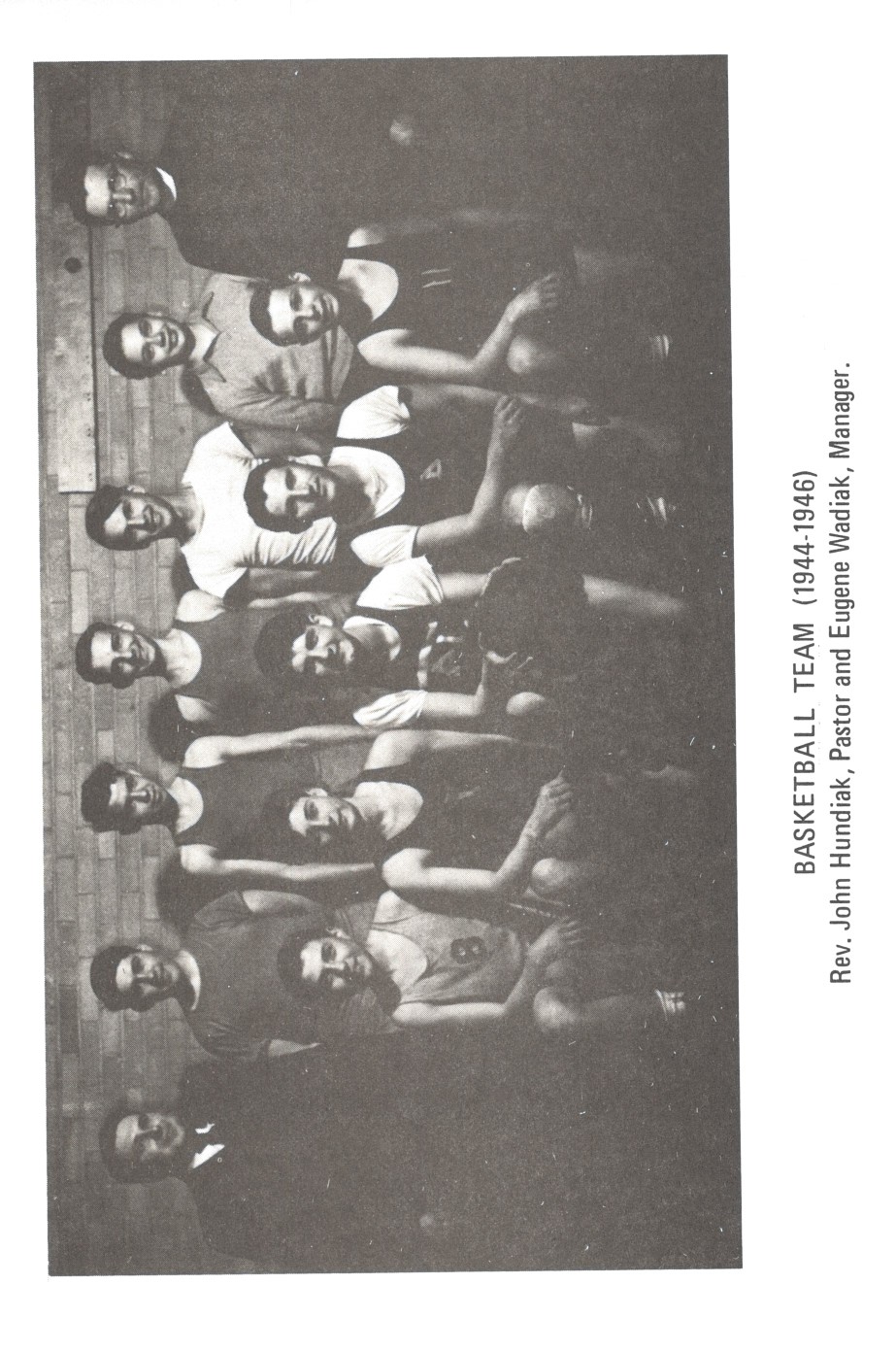

This phenomenon was by no means isolated to Newark. The 1930s and ‘40s (interrupted only by war), Ukrainian teams were playing basketball, softball, baseball, soccer, and even American football in local or church-sponsored leagues all over New Jersey.